The Civil Communication Situation

Humans are social beings. We long for and live in social networks — families, of course, communities, social groups of all kinds, spiritual and religious organizations, places where we labor to support ourselves, and so on. Civil communication helps these groups, these networks of people and organizations, thrive.

We are, in fact, fond of using the noun network as a verb. We network, in ways that serve our primal and social needs. The Web allows networking with people in remote places, instantaneously.

We are, in fact, fond of using the noun network as a verb. We network, in ways that serve our primal and social needs. The Web allows networking with people in remote places, instantaneously.

The instantaneity of technology makes humane, clear, civil communication ever more difficult and of ever more crucial importance.

Even though we now communicate in modes classical thinkers never dreamed of, the principles of civil communication remain similar to those defined by the Western world’s great classical scholars, Plato and Aristotle, who wrote their treatises over two thousand years ago. Their thoughtfulness serves us well today, even though new technologies allow us to communicate face-to-face over great distances, simultaneously with numerous speakers.

Regardless of the communication situation, fundamentals still operate:

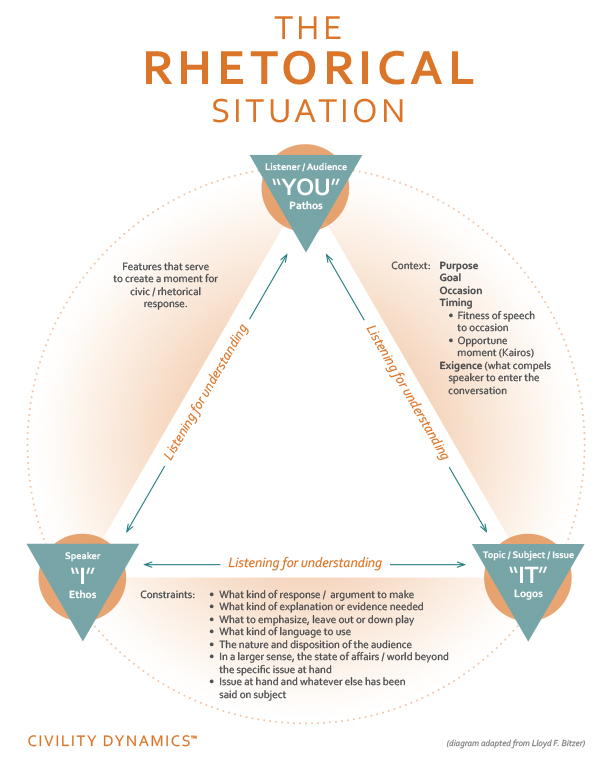

I build here on the thinking of two contemporary scholar-rhetoricians to complete our understanding: Lloyd Bitzer lays out the elements in “The Rhetorical Situation,” and James Moffet applies them in “I, You, It” (see website bibliography).

As we seek civility, I return to the neologism that captures what the situation conveys — IYouIt. I have helped my students and myself remember these complexities by actually writing them down on the palm and fingers of my hand. I suggest you do the same. The act of writing them down and holding them before you as you go about your day helps you to remember them. You hold five elements in your hand — I, You, It, Context, Constraints. Let us think of

Once you have written all of this down, try analyzing dynamic situations in retrospect to understand what happened and why. Most important, think through your own behavior in that instance, as well as that of the other. You will remember and understand the dynamics better if you write your insights down.

Aristotle helps us further understand the complexities of IYouItCC with three ways to appeal to an audience: ethos, pathos, and logos (see graphic once again.) These appeals emanate from I/Speaker. They help us further understand the complexity that is IYouItCC.

You may recognize English words that have roots derived from them: ethics/ethos; sympathy and empathy/pathos; and logic/logos. These concepts overlap and interrelate, as we will see. Aristotle called these concept the appeals. They give a sense of I/Speaker’s presence that we addressed as part of mindful awareness in the very first step to civility. (Recall our neologism, bodyheartmindsoul, that represents us in presence, in our full humanity.) As we discussed in the listening section above, the space between the speaker and audience here is alive with the connotative value of the appeals — what we might think of as the emotive, vibrational values of ethos, pathos, and logos.

I as Speaker project a presence that embodies ethos, surely a desirable quality for civility. I am ethical. I am morally good. I do not harm people or the environment in which they live. I am true to my word. I, with all that is encompassed in my humanity, am accountable.

Pathos connects I as Speaker to You as Audience by appealing to emotions. I as Speaker want to impact your state of mind. I want to influence your emotional responses to me as speaker, and to my topic. Put another way, in projecting ethos, I as Speaker recognize your experiences and the human drama of your life. I acknowledge your story. I, embracing civility, bring pathos to the drama and suffering that is part of your story. I in my full humanity recognize you in your full humanity.

I as Speaker make a final appeal is to logos, or logical proof, what we refer to in more ordinary terms as reasoning. I reason well about It/the Topic. What is more, the ethical and empathic overlay of logos promises that the logic will hold accountability; that is, I as Speaker holds myself accountable for what I am saying. Not lying. Not overstating. Not obfuscating. Being present in the drama of the issues at hand.

In summary, in attempting to persuade you through my appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos, you can count on my being civil. I am worthy of your trust.

The paragraphs above represent a brief if complex lesson in the communication situation. The graphics, on paper and in hand, will extend your understanding. By putting them into practice you will achieve clarity in finding common ground and interacting in common cause.

Regardless of the communication situation, fundamentals still operate:

- I communicate to You on a Topic or Subject (It). IYouIt, — scrunching the words together into a neologism, a new word, to conceptualize them as an entity.

- IYouIt relies on Context and Constraints — add two C’s, as in IYouItCC.

- IYouItCC = I speak to You, the listener, about It, building on situational Context and Constraints.

I build here on the thinking of two contemporary scholar-rhetoricians to complete our understanding: Lloyd Bitzer lays out the elements in “The Rhetorical Situation,” and James Moffet applies them in “I, You, It” (see website bibliography).

As we seek civility, I return to the neologism that captures what the situation conveys — IYouIt. I have helped my students and myself remember these complexities by actually writing them down on the palm and fingers of my hand. I suggest you do the same. The act of writing them down and holding them before you as you go about your day helps you to remember them. You hold five elements in your hand — I, You, It, Context, Constraints. Let us think of

- our hand as the communication situation itself,

- with I, myself in presence, as the opposable thumb that is as crucial to the development of a civil interaction as it was to the development of humankind;

- with You, my listener/reader as the pointer finger, the second digit;

- with It, the topic and its accompanying issues as the third finger;

- with Context as the fourth finger, and

- with Constraints as the fifth finger.

Once you have written all of this down, try analyzing dynamic situations in retrospect to understand what happened and why. Most important, think through your own behavior in that instance, as well as that of the other. You will remember and understand the dynamics better if you write your insights down.

Aristotle helps us further understand the complexities of IYouItCC with three ways to appeal to an audience: ethos, pathos, and logos (see graphic once again.) These appeals emanate from I/Speaker. They help us further understand the complexity that is IYouItCC.

You may recognize English words that have roots derived from them: ethics/ethos; sympathy and empathy/pathos; and logic/logos. These concepts overlap and interrelate, as we will see. Aristotle called these concept the appeals. They give a sense of I/Speaker’s presence that we addressed as part of mindful awareness in the very first step to civility. (Recall our neologism, bodyheartmindsoul, that represents us in presence, in our full humanity.) As we discussed in the listening section above, the space between the speaker and audience here is alive with the connotative value of the appeals — what we might think of as the emotive, vibrational values of ethos, pathos, and logos.

I as Speaker project a presence that embodies ethos, surely a desirable quality for civility. I am ethical. I am morally good. I do not harm people or the environment in which they live. I am true to my word. I, with all that is encompassed in my humanity, am accountable.

Pathos connects I as Speaker to You as Audience by appealing to emotions. I as Speaker want to impact your state of mind. I want to influence your emotional responses to me as speaker, and to my topic. Put another way, in projecting ethos, I as Speaker recognize your experiences and the human drama of your life. I acknowledge your story. I, embracing civility, bring pathos to the drama and suffering that is part of your story. I in my full humanity recognize you in your full humanity.

I as Speaker make a final appeal is to logos, or logical proof, what we refer to in more ordinary terms as reasoning. I reason well about It/the Topic. What is more, the ethical and empathic overlay of logos promises that the logic will hold accountability; that is, I as Speaker holds myself accountable for what I am saying. Not lying. Not overstating. Not obfuscating. Being present in the drama of the issues at hand.

In summary, in attempting to persuade you through my appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos, you can count on my being civil. I am worthy of your trust.

The paragraphs above represent a brief if complex lesson in the communication situation. The graphics, on paper and in hand, will extend your understanding. By putting them into practice you will achieve clarity in finding common ground and interacting in common cause.